The Laibach Story So Far…

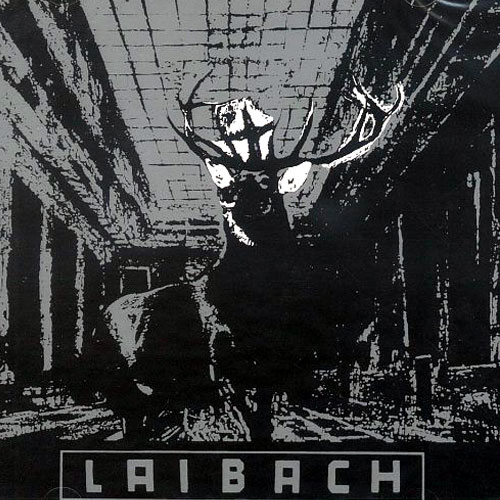

Laibach is a music and cross-media group from Slovenia established on the 1st of June, 1980 in Trbovlje. The name of the band is the historic German version of the name Slovenia’s capital Ljubljana. From the start Laibach has developed a “Gesamtkunstwerk” – multi-disciplinary art practice in all fields ranging from popular culture to art (collages, photo-copies, posters, graphics, paintings, videos, installations, concerts and performances). Since their beginnings the group was associated and surrounded with controversy, provoking strong reactions from political authorities of former Yugoslavia and in particular in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. Their militaristic self-stylisation, propagandist manifestos and totalitarian statements have raised many debates on their actual artistic and political positioning. Many important theorists, among them Boris Groys and Slavoj Žižek, have discussed the Laibach phenomenon both from an analytical as well as critical cultural point of view.

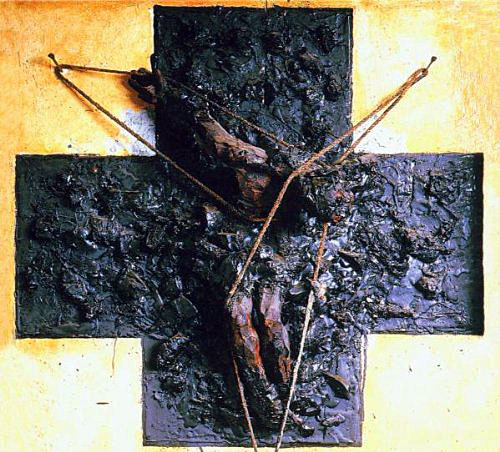

The main elements of Laibach’s varied practices are: strong references to avant-garde art history, nazi-kunst and socialist realism for their production of visual art, de-individualisation in their public performances as an anonymous quartet dressed in uniforms, conceptual proclamations, and forceful sonic stage performances – mainly labelled as industrial (pop) music. Laibach is practicing collective work, dismantling individual authorship and establishing the principle of hyper-identification. In 1983 they have invented and defined the historic term ‘retro-avant-garde’. They creatively questioned artistic ‘quotation’, appropriation, re-contextualisation, copyright and copy-left. Although starting out as both an art and music collective, Laibach became internationally renowned foremost on the music scene, particularly with their unique cover-versions and interpretations of hits by Queen, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, etc.

In 1984 Laibach initiated the founding of the wider collective of NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst) together with the painters from the group Irwin and the theatre group Scipion Nasice Sisters. This led to the establishment of a strong platform for social, cultural and political activity within the climate of liberalisation and pluralisation in 1980’s Yugoslavia. NSK existed as a synchronised movement till 1992, later partly changing itself into a virtual NSK State in time. Limited collaboration between the groups continued till 1995 and beyond.

After the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, Laibach continued mostly within the realm of popular music, while remaining a point of reference in terms of artistic cultural criticism. During recent years the group underwent an international re-evaluation of their artistic practice in the course of an emergence of post-structuralist views on worldwide conceptual art production.

1980 – 1985

Laibach was formed in 1980 shortly after the death of Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the Yugoslavian post-war leader who had spent his political career establishing the principles of non-alignment within the 3rd, 2nd and 1st world and especially within communism. His death initiated a period of uncertainty in Yugoslavia, resulting in power struggles between conservative nationalist hard-liners and more liberal politicians; a period, which saw struggles and disagreements between the different republics constituting Yugoslavia. Laibach’s response to this confusion was to present their group as a totalitarian organization whose zeal for authority far outstripped that of the state. They announced their formation and activities through poster campaigns around the Slovene cities of Trbovlje and Ljubljana, utilizing elements of National Socialism and Socialist Realism propaganda imagery coupled with partisan folk art to create a startling effect. Confronted by these powerful images and the fact that Laibach is actually the German name for Ljubljana, Slovenes were forcefully reminded of their own wartime past under the Nazi and Italian occupation during World War Two.

Hailing from the small city of Trbovlje (16.000 inhabitants), in a region known for its industrial landscapes, mines and political activism, Laibach members were determined to keep this tradition of agitation alive and wilfully baited the Yugoslavian government at every opportunity. This was evident in their first outing in September 1980 when they staged a show called “Rdeci revirji” (Red Districts – popular name for the Trbovlje region, where Slovenian communist party was created back in 1937). This event was scheduled to take place in their home city with the sole intention of challenging a number of contradictions that the group saw as being inherent for the town’s political structures at that time. Not surprisingly this provocative project was banned before it had even opened, on the grounds that it incorporated an inappropriate use of symbols, an accusation that was made constantly during Laibach’s early history.

The state intervened on the second year of Laibach’s existence, too, when their compulsory military service prevented the group from staging any projects during 1981 except for a minor retrospective exhibition mounted in Belgrade’s Student Cultural Centre that featured painting, graphic works, articles and a presentation of Laibach’s music. Re-emerging in 1982, the group resumed their radical operations with an added zeal, staging their first concert in Ljubljana and following it with shows elsewhere in Yugoslavia before returning for a confrontational headline appearance at Ljubljana’s Novi Rock festival in the centre of the city in September. Dressed in stark black and grey (mainly Yugoslav army) uniforms, Laibach performed ferocious noise assaults before a backdrop of totalitarian regalia and wartime slides with political speeches from Tito, Jaruzelski, Mussolini, and others spliced into the mix. Playing in front of aggressive hostile crowds was not without its risks as lead singer Tomaž Hostnik discovered after a bottle struck him during the show. Although bleeding from a facial wound he showed no reaction and the photograph of the wounded Hostnik is now one of the most iconic Laibach images. Unfortunately, Hostnik never performed to more appreciative audiences as in December 1982 he took his own life.

Determined to continue the work that Hostnik had helped to begin, in June 1983, the group made their first television appearance in an interview on the current affairs programme TV Tednik (TV Weekly). Wearing military fatigues and white armbands bearing a simple black cross, Laibach were interviewed in front of graphic images of large political rallies more than a little reminiscent of those in Nuremberg whilst reciting their “Documents of Oppression”. Their flirtation with such controversial imagery once again revealed uncomfortable similarities between Fascist and Socialist Realist iconography; similarities which instantly posed questions about the freedom of the media and the message. Their extremely provocative appearance on this program prompted the show’s host to brand them “enemies of the people”, appealing to respectable citizens everywhere to intervene and destroy this dangerous group.

In the same year Laibach announced their highly important manifesto, “The 10 Items of the Covenant”, first published in Nova revija(No. 13/14, 1983), a Slovene magazine for cultural and political issues. Here the group describes itself as a collective, practicing anonymity, with membership hidden under the four names: EBER, SALIGER, KELLER & DACHAUER. Members of the group still use these pseudonyms and avoid the use of their individual names.

Government officials and politicians had also watched the group’s TV debut and in response to a wave of outrage they banned all planned public appearances in Slovenia and even the use of the name Laibach. Undeterred, Laibach spent November and December of 1983 on their first European tour, called “Occupied Europe Tour”, playing shows that eventually visited 16 cities in eight countries in Eastern and Western Europe. During the intervening years Laibach played a cat-and-mouse game with the various authorities that seemed embarrassed and confused by this group explicitly calling on and provoking them to exercise their authority more harshly. However their desire to agitate regularly created problems for them as the group discovered when the Czechoslovakian authorities refused to allow them into their country. In Poland they were branded as communists and elsewhere in Europe were suspected of being fascists, but these controversies successfully sparked wider interest in their musical output.

Despite the total ban on their performances in their native Yugoslavia, the group made a successful anonymous appearance at the Malci Belic Hall, Ljubljana, in December 1984 (later released on the M.B. December 21, 1984 CD) before co-founding Neue Slowenische Kunst (New Slovenian Art), a guerrilla art collective and movement, created from the union of three groups, namely Laibach, Irwin – the visual artists collective – and the Scipion Nasice Theatre. Neue Slowenische Kunst had some reference to the historic Slovenian avant-garde movement from the 30’s (presented in pre-war Berlin as the Junge Slowenische Kunst) but it was mainly based on the original Laibach Kunst aesthetic, ideas and ideological principles and came about very much as a result of the fact that Laibach was then officially forbidden.

This alliance was spurred on by radical politics and their desire to challenge the contradictions of the status quo in their homeland and beyond. This prompted the formation of a number of NSK sub-groups working in various media but always revolving around the main three. Through NSK, they began addressing the nationalist aspirations surfacing in Yugoslavia, most notably with the spectacular NSK theatre presentation Baptism Under Triglav (Laibach’s soundtrack is available in a lavishly illustrated set that was released by Sub Rosa/Walter Ulbricht Schallfolien). Baptism is also the best illustration of the NSK retro-garde method, which is based on the belief that traumas from the past affect the present and the future can only be resolved by returning to the initial conflict. Neue Slowenische Kunst ceased to exist between 1992 and 1995, but the somewhat utopian project of the NSK State in Time, proclaimed in 1992, still continues till today, carried out by separate groups and diverse citizensof the state.

|

|

|

The Joy Formidable |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Elliot Minor

Charity Workers Massacred |

|

|